The second in a series of posts about the images that have changed the way we understand and make use of the natural world.

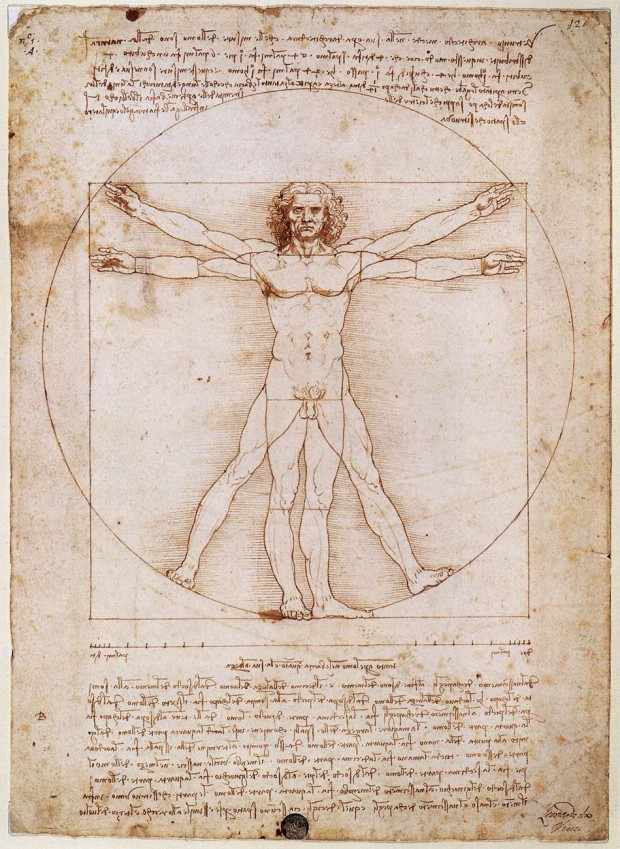

The Uomo Vitruviano of Leonardo da Vinci, drawn about 1487�90, resides today in the Galleria dell’Accademia of Venice. In this iconic image, Leonardo worked out relations of the proportions of the (male) human body as postulated by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius:

In the human body the central point is naturally the navel. For if a man can be placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a pair of compasses centered at his navel, the fingers and toes of his two hands and feet will touch the circumference of a circle described therefrom. And just as the human body yields a circular outline, so too a square figure may be found from it. For if we measure the distance from the soles of the feet to the top of the head, and then apply that measure to the outstretched arms, the breadth will be found to be the same as the height, as in the case of plane surfaces which are completely square.

Artists had tried to match Vitruvius’ prescription with an image, but no satisfactory solution had been found; Leonardo worked out the simple device of spreading the legs to bring the feet to rest within the circle. The resulting design is often taken as a visual demonstration of Protagoras‘ statement that “man is the measure of all things”�although to Leonardo and modern culture, that phrase means something different from what it meant to the ancient Greeks, for whom it was a formula of radical relativism. To Protagoras, each human being was the ultimate measure of his or her own individual world, with no one privy to transcendent standards of truth, beauty, or justice. In the medieval culture into which Leonardo was born, human beings in their incompleteness and ignorance were the compromised evidence of a fall from grace. The renaissance that Vitruvian Man helped to bring about was above all a rehabilitation of the human being as the pinnacle of creation and the expression of a divine ideal.

Leonardo made his drawing about two years before Columbus’ first landfall in the Americas; with the discovery of new cultures and ideals that followed, the notion of a single human ideal would be put to the severest test. And yet as an image of the human body as an expression of nature above all, Leonardo�s Vitruvian Man evinces an emergent world view that will come to be called scientific. It�s also a reminder of the strong connection between art and science that existed in the renaissance�a connection long severed, now undergoing a renascence of its own in the digital age.

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More