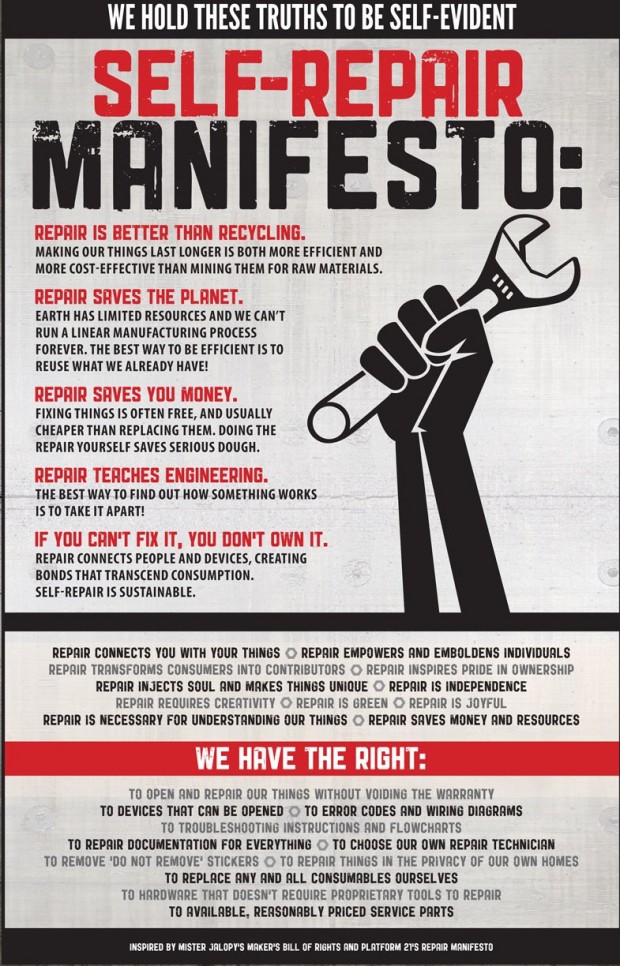

“Repair is green�repair is joyful�repair injects soul and makes things unique.” Those are some of the claims of ifixit‘s Self-Repair Manifesto, which is not a self-help tract but a hacker’s call to arms. Pointing out the economic, ecological, and personal benefits of repairing and remaking, the Self-Repair Manifesto argues that “if you can’t fix it, you don’t own it.”

It’s a plangent appeal in a time when black boxes and planned obsolescence rule the world of gadgets. The new MacBook Airs come with the sealed cases endemic to Apple products, while automotive on-board software locks out independent garages. Planned obsolescence, a term first proposed by Bernard London in 1932 as a scheme to kickstart consumer spending and end the Great Depression, runs amok in the postmodern world. Depression-haunted consumers, London argued, were “disobeying the law of obsolescence…. using their old cars, their old tires, their old radios and their old clothing much longer than statisticians had expected.” London’s answer to this vexing frugality was to propose a tax to be levied on the continued use of consumer goods after they had reached an age agreed upon by government and industry. While London’s draconian notion was never adopted, he didn’t realize that manufacturers like General Motors had already instituted a progressive version of the tax�levied in the form of constant innovation.

Inspired by Mister Jalopy’s 2004 “Maker Bill of Rights”, the Self-Repair Manifesto shares in the liberty-of-tools ethos expressed in Shop Class as Soucraft, philosopher and motorcycle mechanic Matthew B. Crawford’s 2009 paean to repair. Ifixit, which produces crowdsourced repair manuals from toasters to the Roomba and the Wii, wants hackers and aspirational repairers to print copies of the manifesto and put them up everywhere.

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More