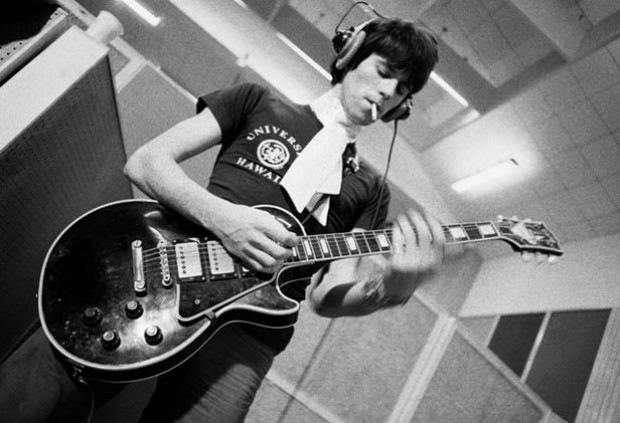

That grinding dirty sound came out of these crummy little motels where the only thing you had to record with was this new invention called the cassette recorder….Suddenly you had a very mini studio. Playing acoustic, you’d overload the Philips cassette player to the point of distortion so that when it played back it was effectively an electric guitar. You were using the cassette player as pick up and amplifier at the same time. We were forcing acoustic guitars through a cassette player, and what came out the other end was electric as hell.

That’s Keith Richards in his autobiography [amazon link=”031603438X” title=”Life“], quoted by Phil Patton in a great Change Observer post about the ever-changing textures that musicians create using disruptive recording technologies.

When Edison perfected sound recording technology in the late nineteenth century, he didn’t even think people would use it for music; the sound quality could never compare to live performance. Gramophones, he reasoned, would be most useful for business dictation and preserving historic speeches. What he didn’t count on was the fact that poor sound quality is a quality?and with changing cultural sensibilities, it would come to be a sought-after quality. And as Patton notes, musicians quickly went from listening to recorded sounds to making music with them. “Recording,” he observes, “did for music what writing did for literature.”

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More