In theory, science and the ancient practices of feudalism are incompatible, if not antagonistic: the one relies on evidence and submits all authority to rigorous, blind experimental testing; the other marshals hereditary power and the prerogatives of property. In practice, howeverm many scientists have claimed elements of Europe’s traditional trappings of power.

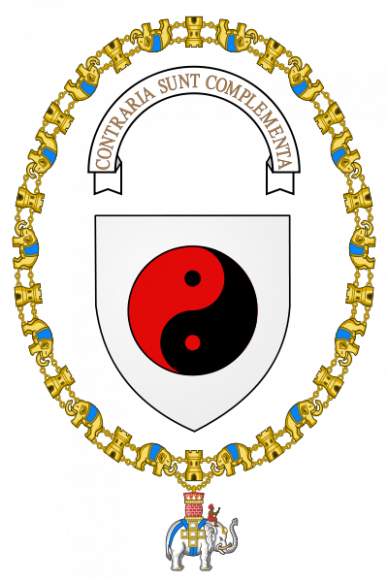

The web site Escutcheons of Science provides an exhaustive guide to the coats-of-arms claimed by major figures in the history of science. In some cases, the arms are hereditary devices that mark their holders as scions of famous families; in other cases, scientists have formulated heraldric iconography to buttress their social standing or in response to aristocratic honors�as was the case with Niels Bohr, the Danish physicist, who was required to create a coat of arms for himself when he was knighted. Bohr incorporated the taiji or yin-yang symbol, which to him represented the complementarity at the heart of physical laws�a principle summed up in his Latin motto, “Contraria Sunt Complementa.” (The elephant-and-castle necklace represents the Danish Order of the Elephant.) The official version of Bohr’s arms hangs in Denmark’s Frederiksborg Castle.

Many of the crests documented at Escutcheons of Science consist of more traditional heraldric iconography�like that of Marie Curie, whose Sklodowski family crest is described as “Azure, an arrow [point downwards] within a horseshoe Argent surmounted by a cross patty Or.” And then there’s Sir Isaac Newton’s rather wonderful device, a crossbones�in heraldric language, “sable, two shinbones in saltire Argent (the dexter surmounted of the sinister).” Newton’s crest seems like the kind of design a convention-busting mad scientist might have chosen for himself (Newton, born the year following Galileo’s death, was the first scientist to receive a knighthood); in fact, the design was a hereditary device of the Newton family, seen here on the wall of the scientist’s ancestral home, Woolsthorpe Manor.

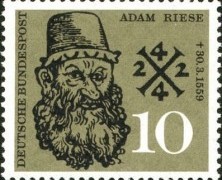

But other scientists have long preferred Bohr’s more freewheeling approach. Adam Riese, a sixteenth-century German mathematician credited with popularizing the so-called Arabic numerals in place of Roman numerals for calculation, included the numbers 2 and 4 in his simple crest�reproduced on a stamp by the West German Bundespost on the four-hundredth anniversary of his death.

[thanks, @jessamyn!] Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More

Gearfuse Technology, Science, Culture & More